‘It’s Horrendous’: The Deaths Of 2 Doctors Deepen The Void In Rural Health Care Access

Molokai General Hospital is one of three health care providers on Molokai that is absorbing new patients following the deaths of two primary care doctors. Cory Lum/Civil Beat/2021

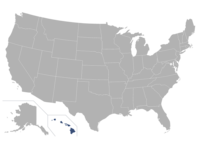

Doctors have long been in short supply on Molokai, where residents must board a plane to access specialized care and routine treatment is propped up by a revolving door of fly-in physicians.

But for decades primary care on this island of fewer than 7,000 residents was buoyed by a pair of family medicine physicians who embedded themselves in the community, providing comprehensive, day-to-day health care to nearly half the population.

Then came an unexpected hurdle: They died.

In a span of three months late last year, Dr. William Longfellow Thomas, 57, and Dr. Noa Emmett Aluli, 78, died, leaving thousands of Molokai patients without a primary care physician.

No one is waiting in the wings to replace them.

“We’ve lost these physicians who lived and worked there for decades and who chose that remote, rural lifestyle, and we are incredibly appreciative of what they’ve sacrificed to do that,” said Hilton Raethel, chief executive officer of the Healthcare Association of Hawaii that represents the state’s hospitals and other health care facilities. “But going back to this issue of where do you get new physicians, it’s like why would a young or middle-aged physician go and work on Molokai when they could work on any other island? It’s going to be very, very challenging.”

Hawaii has the equivalent of 2,856 full-time doctors. But the state estimates it needs an additional 776 physicians to meet patient demand, according to a 2022 annual report that tracks Hawaii’s medical professional needs. The greatest shortage is in primary care, with 162 doctors needed across all islands.

On Molokai, where about 60% of the island’s residents are on Medicaid, there are now fewer than four full-time primary care physician equivalents, according to Kelley Withy, a medical doctor and professor at the University of Hawaii’s John A. Burns School of Medicine.

Since the sudden and stacked losses of Thomas and Aluli, there has been about a 50% decrease in physician services available on Molokai, Withy said. Of the doctors left, more than half are of retirement age.

“We have never had this big of a drop, and this abruptly, in the medical workforce,” Withy said. “It’s just horrendous.”

In addition to the two physician deaths, another doctor on the island is expected to retire sometime this year, according to Raethel.

Aluli, who saw patients on the day he died, provided care to more than 1,700 Molokai residents, according to Donna Gamiao, Aluli’s nurse and officer manager.

By several accounts, Aluli was a portrait of the old-school country doctor. He visited patients at home, ushered in drop-in and after-hours patients and forged trust in families over generations. His research into traditional Hawaiian foods culminated in the Molokai Heart Study, which used diet to address poor health outcomes from heart disease, diabetes and obesity.

“When you think about a country doctor who comes to see your grandmother at home, who sees patients if they just show up without an appointment — you can’t put a price tag on this,” said Kimberly Svetin, president of family-owned Molokai Drugs and a patient of Aluli. “I mean, he was invited to his patients’ birthday parties and funerals. I don’t ever think we’re going to see a doctor like him on Molokai again.”

Thomas, who worked at Molokai General Hospital, told Honolulu Magazine that he was inspired by the heartfelt way in which Aluli spoke about rural medicine to launch his own medical career on Molokai.

Outside of medicine, Aluli was a pillar of the Hawaiian sovereignty movement. He was one of the so-called “Kahoolawe Nine” activists who on Jan. 4, 1976, made the first landing on Kahoolawe to protest the island’s use as a bombing range by the U.S. Navy.

Molokai Family Health Center, Aluli’s clinic, will permanently close its doors Wednesday. Medical staff from the hospital, as well as doctors flown in from Queen’s University Medical Group on Oahu, have been providing interim care for Aluli’s former patients.

At least a couple of Aluli’s former patients have transferred their care to an Oahu-based doctor, Gamiao said. Some patients have been absorbed by the island’s three other health care clinics. Others have not established care with a new primary care doctor yet.

The only alternative to a primary care doctor on the island is the emergency room of Molokai General Hospital. But the use of an ER to treat routine or relatively simple health problems is not ideal, not only because it typically costs patients more money. It can also strain a health care system designed to address acute problems like heart attacks and strokes if people are coming in with minor issues like headaches or an upset stomach.

Molokai General Hospital did not return requests for comment.

A statewide doctor shortage is the consequence of myriad factors, not the least of which is Hawaii’s high cost of living and limited medical training opportunities.

On Molokai, the problem is exacerbated by the island’s disproportionate percentage of patients on Medicaid, the government’s safety net insurance program for low-income people. Nearly two-thirds of the island’s residents are covered by Med-QUEST, the state’s version of Medicaid, compared to about a third of all Hawaii residents.

Hawaii has some of the lowest reimbursement rates for Medicare in that nation, and the Medicaid fee schedule is currently set at about 60% of Medicare, according to Raethel. Medicaid reimbursement rates in Hawaii are sometimes so low as to barely cover the cost of care.

The Healthcare Association of Hawaii is lobbying state legislators to set aside $30 million in annual state general funds to eliminate the reimbursement gap between Medicaid and Medicare. The state funds would be eligible for a federal match for a total annual investment of $71 million, which would allow any Hawaii medical professional who bills Medicaid to receive 100% of the Medicare fee schedule — a big boost from the current rate of about 60%.

The legislation is sponsored by Sen. Joy San Buenaventura and Rep. John Mizuno, Raethel said. The Legislature opened its 2023 session on Wednesday.

Another issue: On an island where more than a third of the residents report that they farm, hunt and fish to keep fed, the lifestyle eschews many of the trappings of modern life. There is no movie theater, mall or McDonald’s, for example. Some neighborhoods are outside of cell-service range.

“We’re very humble on Molokai,” said Rosie Davis, executive director of Huli Au Ola Area Health Education Center, which strives to be a high school-to-medical school pipeline for Molokai students. “We can’t run to the big grocery store or the 24-hour drive-though, which we don’t miss, but if you’re not used to this lifestyle there’s not a lot of options, not a lot of choice, and unemployment is high.”

Aluli tried throughout his 47-year-practice on Molokai to lure new doctors to the island, in part by taking on medical students as interns and trainees, exposing them to the unique rewards, challenges and day-to-day dynamics of rural medicine.

“I think the biggest tragedy is that he tried to secure a succession plan,” said Miki‘ala Pescaia, who said Aluli treated three generations of her family. “He did everything he possibly could have done to set us up to avoid this moment and the fact that we’re here is the most painful thing.”

Last summer Kamalei Davis, the 22-year-old daughter of Rosie Davis, shadowed Aluli at his Molokai practice for a week, an experience she credits with fine-tuning her understanding of a rural family medicine doctor’s comprehensive understanding of his patients.

“He really knew all his patients, and not only that but he knew generations of their family and he knew how they lived and what they did for a living,” she said. “That was something that just amazed me.”

Kamalei Davis was about 6 years old when she declared she would one day be a pediatrician after she learned there was such a thing as doctors who focus on the health of children and adolescents.

“Ever since I figured out what a pediatrician was and how we didn’t have that on Molokai, I was determined to fill that gap because that’s something I would have wanted to experience as a child,” said Kamalei Davis, who was accepted into a Missouri medical school last week.

She said she doesn’t blame doctors who cycle in and out of Molokai, unable to adjust to life on an island without traffic lights. But as a native of the island who enjoys hunting, fishing and other trademarks of subsistence living, she doesn’t view the island’s lack of modern amenities as a sacrifice.

But on the verge of her first semester in medical school, Kamalei Davis said she may not pursue her lifelong dream of practicing pediatrics after all. Instead, she’s thinking about becoming a family medicine doctor so that one day she can return to Molokai to help patch the island’s most dire medical workforce gap.

Civil Beat’s coverage of Maui County is supported in part by grants from the Nuestro Futuro Foundation and the Fred Baldwin Memorial Foundation.

Civil Beat’s health coverage is supported by the Atherton Family Foundation, Swayne Family Fund of Hawaii Community Foundation and the Cooke Foundation.