What does history tell us about how the Idaho Supreme Court might rule on abortion?

Idaho drafted its original abortion statute at the First Territorial Session in Lewiston — 25 years before Idaho became a state and drafted the state constitution — in the winter months between December 1863 and early 1864.

The wording of the statute is almost identical to statutes several other states were passing to ban abortion around the same time, including Montana and Nevada.

Like the ban that took effect in Idaho in August, that law allowed for abortion to save the woman’s life, but not for rape and incest.

Between 1864 and 1973 — when the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling on Roe v. Wade declared a constitutional right to abortion throughout the U.S. — Idaho successfully prosecuted and imprisoned only six people for crimes related to the abortion statute. Three of those were prosecuted because the pregnant woman died following the procedure.

Two additional cases in the 1950s were prosecuted but dismissed for lack of evidence and a hung jury.

That’s according to research from a thesis written by Rosemary Wimberly at Boise State University in 1996. The thesis is one of the only comprehensive studies of abortion in that period of Idaho history. Copies of the thesis are kept at the Idaho State Archives and at Boise State University’s library.

Wimberly wrote that, because of “popular tolerance” of abortion, prosecutors found it difficult to get convictions in cases where the woman did not die as a result of the procedure. American historians point out that, prior to the 1850s, most people were not against abortion prior to “quickening,” the point in a pregnancy when a fetus’s movements can be felt by the pregnant person. That typically occurs around 16 to 20 weeks, in the second trimester.

A few of the convictions were appealed to the Idaho Supreme Court — the same court that is expected to soon rule on whether Idaho’s new abortion bans will remain unchanged.

Many judges see sticking with legal precedent as part of maintaining a stable legal system and don’t want to be thought of as policymakers. But, at the moment, Idaho Supreme Court justices are faced with a difficult decision: break with a legislative history restricting abortion that dates back to Idaho’s territorial days, or interpret the Idaho Constitution’s right to privacy as one that extends to abortion.

Idaho now has in effect a ban on nearly all abortions, with legal defenses allowed for rape, incest and to save the pregnant person’s life. If someone is prosecuted under the existing law, those are acceptable as a defense in court. In the case of rape or incest, the victim must also provide a copy of a police report. The state also enacted a civil enforcement law that is modeled after a similar law in Texas to allow civil lawsuits against medical professionals who perform abortions after fetal cardiac activity is detected, which is typically around six weeks of pregnancy. The law awards no less than $20,000 to the mother, father, grandparents, siblings, aunt or uncle of the fetus or embryo in a successful lawsuit. It includes exceptions for rape, incest or a medical emergency that would cause death or create serious risk of substantial harm to the patient. A third law banned abortion at six weeks of pregnancy, but that law was rendered unenforceable when the near-total abortion ban went into effect. What are Idaho’s current laws on abortion?

Abortion was one of the worst crimes, an Idaho justice wrote in 1901

Planned Parenthood filed separate lawsuits against all three of Idaho’s most recent laws related to abortion. The organization’s attorneys argued before the Idaho Supreme Court in early October that the state’s courts have historically held that, under the Idaho Constitution, there is a fundamental right to privacy and to make familial decisions. Article I of the Idaho Constitution mentions certain inalienable rights, such as enjoying and defending life and liberty, pursuing happiness and securing safety.

Although Idaho’s constitution does provide protection for privacy — and abortion is one of the most private decisions a person can make — justices are likely to take precedent into consideration, said Richard Seamon, a University of Idaho professor who teaches constitutional law. That may be an especially salient point, because without the backing of Roe v. Wade, the state is, in a way, starting from scratch, he said.

“This is a decision that each justice has to make for him- or herself, but I think almost all of the justices agree that they’re bound by precedent, and they have to have a good reason for breaking precedent,” Seamon said in an interview with the Idaho Capital Sun. “Justices who reach the state or U.S. Supreme Court tend to be conservative with a small c, or humble, in a sense. They’re coming into an office where there have been lots of brilliant judges in the past, and they have to kind of approach their task with humility.”

But the cases that were specifically related to Idaho’s abortion statute make it clear how some past justices viewed abortion.

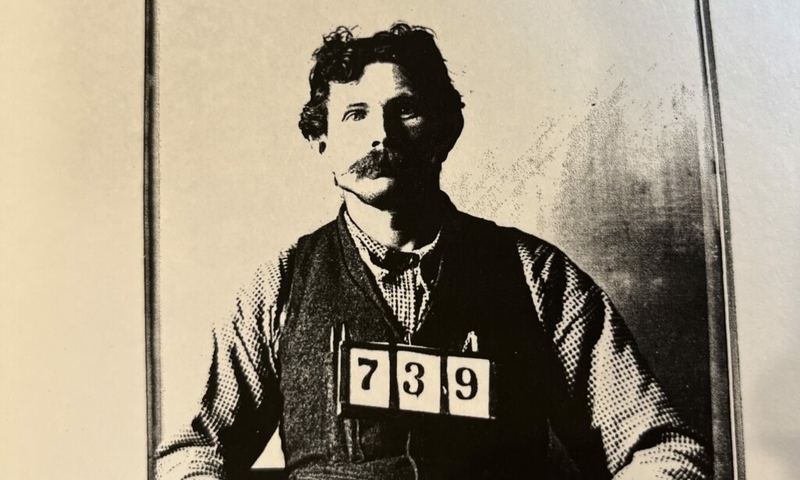

In 1901, a 20-year-old Kootenai County woman named Cora A. Burke sought an illegal abortion from a doctor named E.J. Alcorn. Burke had been a widow for about five months, and already had a 4-year-old son.

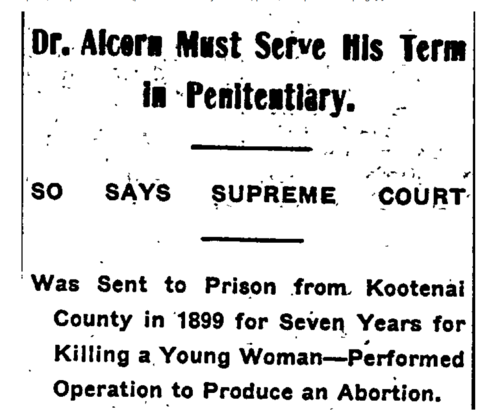

Two days after the procedure, she died of septicemia, or blood poisoning, resulting from infection. Alcorn was charged with manslaughter for the crime and sentenced to seven years at the Idaho Penitentiary. Today, such a death is rare, due to medical advances and antibiotics.

Alcorn’s appeal to the Idaho Supreme Court was denied, and Chief Justice Ralph P. Quarles wrote, “The crime for which appellant has been convicted is one of the worst known to the law. An unnatural abortion, brought about by means of drugs or instruments, violates decency, the best interests of society, the divine law, the law of nature, the criminal statutes of this state, and is not only destructive of life unborn, but places in jeopardy the life of a human being — the pregnant woman.”

Abortions were a hard crime to prove, history professor says

Evan Hart, an associate professor of history at Missouri Western State University, has studied abortion history specific to Missouri and nationwide. She said 20 abortion-related crime cases made their way to the Missouri Supreme Court between the 1860s and 1945, and from her research, Idaho is an outlier in terms of just how few cases were prosecuted.

Hart said abortion laws were rarely prosecuted in part because it was difficult to prove a woman had been pregnant, and because if nothing went wrong and the woman survived, few people were likely to know it occurred; even if they did, they probably weren’t going to report it to authorities.

“Oftentimes police and prosecutors were saying, ‘If they’re not hurting people, if they’re not causing deaths, infections or illness, then we stay out of it,’” Hart said. “Especially before the turn of the century, lots of people still kind of believed, ultimately, that this was not a matter for the courts. If someone died, then yes, it was. But if it’s a familial issue, for a lot of prosecutors, it was like, ‘That’s their business.’”

Quarles seemed to take a tougher stance, based on his opinion in the State v. Alcorn case.

“Both actors, when there are two … are guilty of felony, and ought to be punished by the law, if the woman survives,” Quarles wrote in 1901. “And, if she does not, then the person or persons participating in the abortion should be punished. This crime is one of grave consequences to society. The law prohibits it and prescribes severe penalties. The law ought to be strictly enforced.”

Another Idaho case in 1934 was a civil matter that involved a married couple named Clyde and Jean Nash, who said a doctor named John S. Meyer performed an abortion on Jean Nash that he claimed was necessary to save her life, but the couple said the doctor was negligent and deceitful in his actions. In that case, Chief Justice Raymond Givens wrote about his interpretation of the intent of the statute as written in 1864.

Givens wrote that the abortion statute was designed for the protection of the general public interest, not the protection of the woman. While Idaho’s assault and battery and dueling statutes were designed for the direct protection of the individuals involved, that did not extend to abortion.

“The exception must rest not on the tender care or protection of the statute for the woman, but, generally, that an illegal act is inherently fraught with danger to the life, health and safety of the individual,” he wrote.

Idaho Supreme Court’s ruling is unlikely to be the last word on abortion in Idaho

When the U.S. Supreme Court made its initial decision on Roe v. Wade on Jan. 22, 1973, the Idaho Legislature was in session. According to legislative records and newspaper articles from the Idaho Statesman in the weeks after the decision, legislators from both parties initially argued over whether the state’s abortion law had to change to comply with the new constitutional protection.

A deputy attorney general at the time, Kent Taylor, told legislators they would have to comply with Roe v. Wade, so they agreed to write the most restrictive abortion law possible within the confines of the high court’s ruling.

Some Democratic legislators at the time were staunchly opposed to changing the law, including Sen. E.H. Tacke of Cottonwood, who was quoted in the Statesman saying, “To me, abortion, no matter what trimester, is taking the life of an infant, a creature of God, who has the right to life.” That recent history, coupled with what’s on record from earlier days, could make the decision a difficult one for justices, said Seamon, the University of Idaho constitutional law professor.

“They have to be thinking about how there is a pretty long legislative record of opposition and a restrictive approach towards abortion,” he said. “They would have to break with that tradition, to interpret the Idaho Constitution (as protecting) a right of access to abortion.”

The court doesn’t have to explicitly rule one way or the other, Seamon said, although not addressing the central question of abortion could present other challenges for the court. If the justices determine the way the law is written is the issue — not the idea of restricting abortion itself — that would force the question of which parts of the law are upheld and which aren’t, he said. That would be particularly true with regard to what physicians can or cannot do in dangerous medical situations, he said.

If the court finds any of the law’s provisions to be unconstitutionally vague, it would “essentially send the law back to the Legislature and say, ‘We can’t enforce this as it’s written now because it’s too vague. Go back to the drawing board,’” Seamon said.

The court may also consider the fact that, during the more than 100 years when abortion was strictly illegal in Idaho, it was rarely prosecuted.

“Judges do look at the difference, they realize that the laws on the books often differ from the law in operation. I think a judge would need to take that into consideration,” Seamon said. “But even if the Idaho Supreme Court comes out with some sort of ruling that the Idaho Constitution protects some access to abortion, that’ll just open more doors as to, what are the limits of that right? So there will still be lots of open questions.”