‘Their influence on me is immeasurable’

Betty DeRamus and Susan Watson were “two of the most gifted women in the history of Detroit journalism.”

That’s according to Judy Diebolt, a retired Detroit Free Press and Detroit News journalist who added that it was her “privilege to get to work with both of them.”

DeRamus and Watson, both African American, started reporting in the city in the 1960s and were later inducted into the Michigan Journalism Hall of Fame.

Watson was a reporter and editor who penned a column for the Detroit Free Press. She died in 2020. DeRamus was a reporter at the Black-owned Michigan Chronicle and the Detroit Free Press. She wrote columns for the Detroit Free Press and Detroit News and is now retired and living in Farmington Hills.

Both worked in newsrooms that had few people of color and women on staff.

In 1983, as the women were in the prime of their careers, the Detroit chapter of the National Association of Black Journalists released a survey reporting that 29 white-owned media outlets in Detroit had 1,082 employees and only 137 or 12.6% of them were Black. At the time, the city’s population was 63% African American and the six-county metro area was about 22% Black.

But throughout their groundbreaking careers, DeRamus and Watson have impacted many other journalists like Darren Nichols.

“Their influence on me is immeasurable. I owe my career to them and don’t take it lightly,” said Nichols, who has reported for the Michigan Chronicle and The Detroit News and been a contributing columnist for the Detroit Free Press. “… Betty as a colleague and Susan as a second mom.”

“[Watson] literally introduced me to newspapers,” added Nichols. “I started really reading newspapers because of her. She normalized Black folks in this industry.”

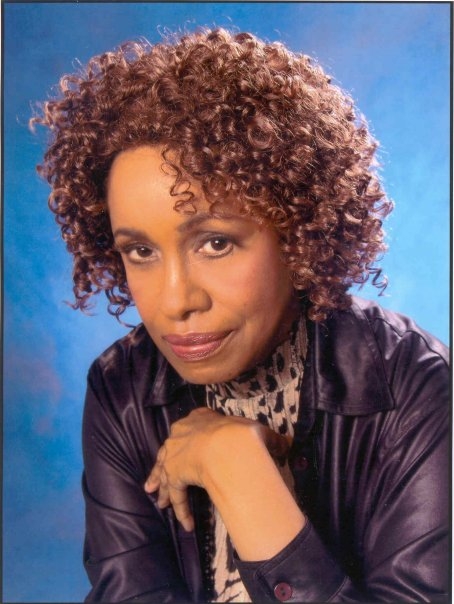

Watson was ‘eagle-eyed, fair, and funny’

Watson, a River Rouge native and University of Michigan graduate, began her career at the Free Press in 1965.

She earned many awards for her work, including several AP and UPI awards for columns and the Heywood Broun Award for her year-long investigation into the abuse of developmentally disabled youths in a state facility. Watson also was honored with the Knight Ridder National Excellence Award in News/Editorial and earned three Emmys for local television commentary. She is a member of Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame.

Watson was “eagle-eyed, fair, and funny,” said retired Detroit Free Press journalist Patricia Montemurri. “She was one of my first editors and a forever mentor. Her nose for news was always on target, and she was fearless when it came to confronting wrongdoers.”

In 1986, Watson in a Free Press column ripped Detroit-area store owners for selling drug paraphernalia.

“Why are you helping to destroy a community by peddling drug accessories that help people get high?” Watson wrote.

“Why are you selling things like gram scales and water pipes and drug cutting tools in a community that already is devastated by drugs?”

Is the profit from these sales so great that you can forget the obscene number of young people and adults who die from drug overdoses or who are shot to death in drug wars?”

Later that year, Watson received an award from Boysville of Michigan Inc., a network of nine homes for 400 teenaged wards of the court or referrals from state agencies.

In 1990, a book that compiled many of Watson’s Detroit Free Press columns was published and at one time you could dial a telephone number at the newspaper and hear Watson read her columns. In 2000, she was inducted in the Michigan Journalism Hall of Fame.

She later worked for U.S. Rep. John Conyers Jr., a Detroit Democrat, and for the Detroit Federation of Teachers as a communications specialist.

“She was my Scrabble partner and she beat me most of the time,” recalled Randye Bullock, a veteran public relations officer. “We played daily for months on end.”

DeRamus: ‘I never thought that I’d done anything above and beyond my job.’

DeRamus wrote a letter to the Detroit Times that “won the award for best article,” according to her seventh grade Sacred Heart School teacher, Sister Bernadine.

She graduated from Wayne State University and landed her news reporting job at the Michigan Chronicle, the state’s largest Black-owned newspaper during the 1960s. Her father was proud of her reporting.

“He used to take her articles to the barber shop and read them to his friends,” according to longtime friend and former Detroit News colleague Denise Crittendon.

DeRamus helped to cover the 1967 civil unrest in Detroit, which has been generally described as Black protest against systemic racial discrimination carried out by a largely white local police department.

She was a reporter and then editorial writer at the Detroit Free Press from 1972 to 1987 until the Detroit News hired her as a columnist. In 1986, the Sigma Delta Chi Foundation awarded her the Eugene Pulliam Fellowship for Editorial Writers. She used the prize money to visit Cuba, Brazil, England, West Berlin, Amsterdam, Finland, Poland and the former Soviet Union.

DeRamus traveled to South Africa in 1990 and penned several stories for the Detroit News about the apartheid era and Nelson Mandela’s release from prison. The experience was one of her many trips to the African continent.

“She has visited more African countries than anyone I know,” said Crittendon, who traveled with DeRamus to Egypt 40 years ago.

In 1995, members of the Newspaper Guild and Teamsters, which includes about 2,000 journalists, pressmen, printers and others, launched a strike after contract negotiations over work conditions and rules with their employer, Detroit Newspaper Agency, broke down.

Daily demonstrations included major civil rights leaders Joseph Lowery, union officials Richard Trumka and Stephen Yokich, as well Detroit political leaders like U.S. Rep. John Conyers (D-Detroit) and Detroit City Council member Maryann Mahaffey.

During the newspaper strike, Watson was active on the picket line and did not return to the Free Press. DeRamus also refused to cross the picket line.

DeRamus returned to the Michigan Chronicle during the daily newspaper strike. In 1997, she became director of the city of Detroit’s Communications and Creative Services Department.

After the unions ended the strike in 1997, she returned to the Detroit News in 1998 and later retired from the paper in 2006.

In 2005, her book “Forbidden Fruit: Love Stories from the Underground Railroad” was published centering on African Americans during slavery in the 19th century.

“The reason I wrote this book,” DeRamus told C-SPAN during a 2007 cable television interview. “It tells the other side of the story about slavery. A side that we never hear. We always hear about people who were separated by the institution families.They were sold apart. And that was differently a part of the story but the thing that engaged me about this project, and about these stories is that these people did just the opposite: They refused to let anything separate them.”

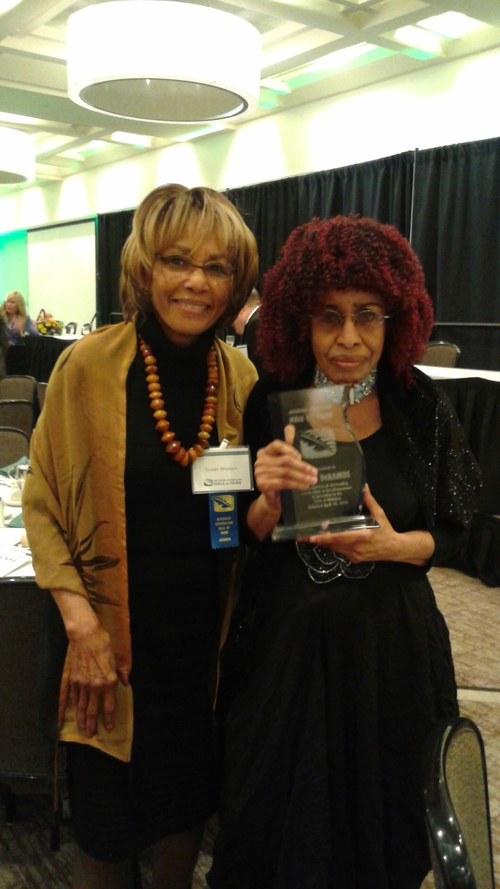

DeRamus was a founding member of the Detroit Chapter of the National Association of Black Journalists. In 2015, DeRamus was inducted into the Michigan Journalism Hall of Fame.

“I never thought that I’d done anything above and beyond my job,” DeRamus told the Detroit Free Press in 2015. “That’s the god’s truth. I’m not being falsely modest.”

DeRamus helped to roast Watson during the Detroit chapter of the National Association of Black Journalists fundraiser in 1991, Bullock recalled. “It takes a special person to agree to be roasted,” said Bullock. “She certainly was special.”

The effort, held at Club Penta in Detroit, raised more than $7,000 for scholarships devoted to aspiring Black journalists, according to a Detroit Free Press report at the time.