Study documents high rates and persistence of colorectal cancer among Alaska Natives

Alaska Natives continued to have the world’s highest rates of colorectal cancer as of 2018, and case rates failed to decline significantly for the two decades leading up to that year, according to a newly published study.

The study, by experts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, compared colorectal cancer rates among Alaska Natives with those of other populations in Alaska, the Lower 48 and other parts of the world.

The 2018 colorectal cancer rate for Alaska natives was 61.9 per 100,000 people, said the study, published in the International Journal of Circumpolar Health. Of the other countries used for comparison, only Hungary – which is consistently ranked as the nation with the highest colorectal cancer rates — had rates rivaling those for Alaska Natives, at 51.2 per 100,000 people.

Colorectal cancer rates among Alaska Natives sharply differ from those for other Alaska demographic groups, the study said. From 2014 to 2018, the Alaska Native colorectal cancer rate was over twice that for Alaska’s white population and over three times that for Alaska’s Asian/Pacific Islander and Black populations, it said.

Among other Indigenous groups in the United States, broken down by Indian Health Service region, colorectal cancer rates were much lower than those for Alaska Natives, the study found. The 2018 statistics showed that Alaska Native rates nearly twice as high as the next highest group, those in the Southern Plains region, and over five times that of the lowest group, which was in the IHS East service region.

The study also tracked an apparent lack of meaningful progress in reducing colorectal cancer rates among Alaska Natives. While rates declined significantly for white Alaskans from 1999 to 2018, by 2.2% percent, the 1.05% decline over the same period for Alaska Natives was not considered to be statistically significant.

The statistics gathered in the study revealed other trends, including gender gaps that were very wide in some countries. Among Hungarian men, the rate was 70.6 per 100,000 people, while for Hungarian women it was 36.8 per 100,000 people, the study said.

In contrast, the Alaska Native colorectal cancer gender gap was smaller, with rates of 63.6 per 100,000 people for men and 59.8 per 100,000 for women.

Exactly why Alaska Natives have such high rates of colorectal cancer remain unclear. Among the possible factors being studied is a diet that is low in fiber from fruits, vegetables or whole grains. Another possible factor is the higher rates of tobacco use.

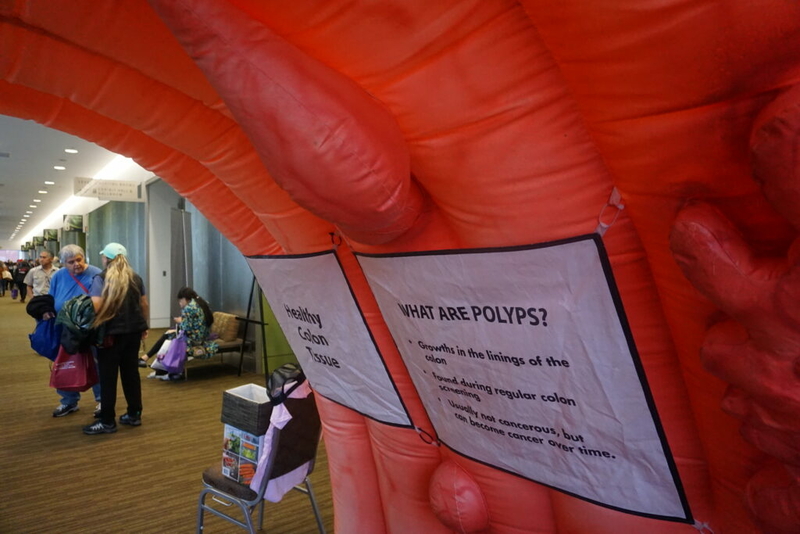

The high incidence of colorectal cancer among Alaska Natives has been a concern for several years. It has spurred health providers to recommend earlier and more frequent screenings for their Alaska Native patients. The ANTHC and Alaska Native Medical Center recommend that colorectal cancer screenings start at age 40, compared to the CDC recommendation of screening starting at 45 for the general population.

The study shows the need for such screening, lead author Donald Haverkamp, a CDC epidemiologist, said by email.

“The important message here is that colorectal cancer affects both men and women and that colorectal cancer screening can help with both prevention and early detection of colorectal cancer. Screening tests can find polyps so they can be removed before developing into cancer. Screening also helps find colorectal cancer at an early stage when treatment works best,” Haverkamp said.

The 2018 statistics were the most recent available at the time the study was written, he said, and the authors used information from the International Agency for Research on Cancer’s Global Cancer Observatory, among other sources. Rates cited in the study were adjusted for age.