Montana students, teachers blast bill that would limit science education to ‘scientific fact’

Several Montana middle- and high-school students said Monday that a lawmaker did not correctly interpret scientific theory and that his bill would ban common theories, like gravity, from being taught in schools – hampering their education and futures in STEM fields.

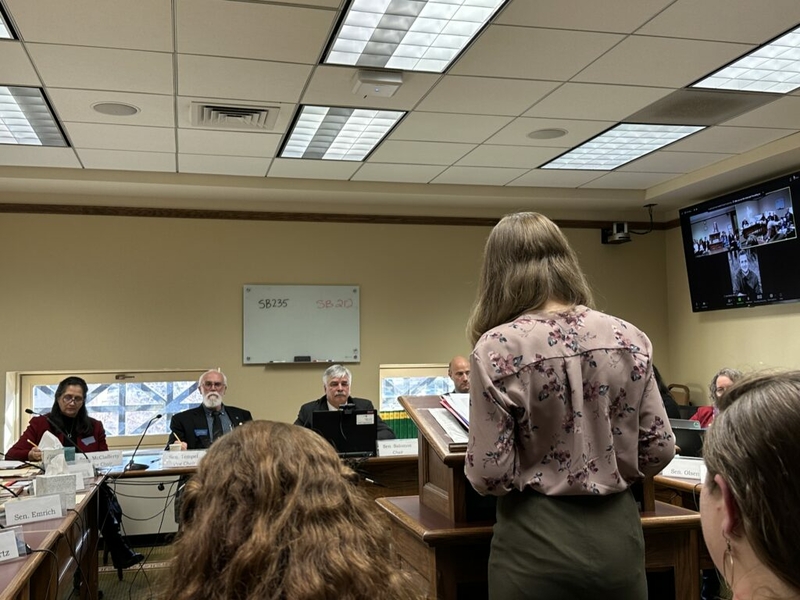

They, along with several award-winning Montana science teachers and representatives from the Board of Public Education and other organizations, testified in opposition to Sen. Daniel Emrich’s Senate Bill 235 in its first hearing Monday at the Senate Education and Cultural Resources Committee.

The bill from the Great Falls Republican seeks to create a new portion of law that states that all science education “may not include subject matter that is not scientific fact.” It would also have school boards review all science materials to be sure they only use “scientific fact” in a “strictly enforced and narrowly interpreted” fashion.

Further, starting in July 2025, it would allow parents to appeal a board’s alleged “lack of compliance” to a county superintendent and the superintendent of the Office of Public Instruction.

However, teachers and students said his bill was little more than a threat to public education and the STEM – or science, technology, engineering and math – community, as well as a poor measure to consider when Montana is trying to recruit more teachers, not lose them.

Most of the hearing centered on educators, students and public education officials telling Emrich that his bill’s interpretation of what a “scientific fact” is – “an indisputable and repeatable observation of a natural phenomenon,” as it states – was not how the scientific community judges theory and fact.

“Science is an ongoing process, and as we continue to question and learn more about our world, the evidence that makes up a theory is added to it. Science education has a responsibility to teach the young people of Montana the true process of science,” said Kimberly Popham, who teaches AP biology and forensic science at Belgrade High School.

“If we don’t teach our students what a scientific theory is, and how we got them, and how it differs from other theories, and that it’s always going to be supported by empirical evidence, we will be doing them a disservice,” she added.

Only one proponent of the measure testified – a man who said he had a law degree and was teaching in South Korea. More than 20 opponents spoke at the hearing.

Rob Jensen, a former Hellgate High School teacher who won the Presidential Award for Excellence in Mathematics and Science in 2019, said he was not exaggerating when he called the bill “the most extreme anti-science legislation I’ve ever seen in this country.”

He said it made a 1925 case in Tennessee involving a science teacher teaching evolution who was put on trial “look like a period of Enlightenment.”

Lindsey Read, a senior at Capital High School in Helena, told the committee the measure would strip teachers of the ability to teach virtually any science. She said she and other students would not be able to learn about atomic theory, cell theory, the Big Bang Theory, or plate tectonics, among others, because they are simply theories.

“Science is not a collection of indisputable facts; rather, it is a series of best explanations,” she said, explaining the difference between scientific theory and the word “theory” as it is commonly used.

She said if the bill were to become law, it would put Montana students far behind their peers in other states – something echoed by multiple others who testified.

They said whether students were pursuing higher education or not, the base-level scientific knowledge taught in Montana schools is necessary to both understand the world and pursue professional opportunities in countless fields.

“Science is not only taught in a science classroom. It is taught in math; it is taught in history. Because science is not a monolith. It exists throughout a student’s education,” Read said.

Mia Taylor, a sophomore at Helena High, worried that her younger cousin would not get the quality education she said she is receiving, telling the committee that there were no scientific facts that did not start out as theories.

Greysen Kakes, a seventh-grade student at Helena Middle School, said it was his dream to be involved in the sciences and that SB235 would put him – and those who are not pursuing a higher education – at a disadvantage heading into their post-high school careers or colleges because he hadn’t learned basic concepts.

“Not teaching these theories would stifle innovation as we move backwards in science education while the rest of the country moves forward, and the people who would suffer most would be Montana youth such as myself,” he said.

Parents, educators and a legal review of the bill also said the bill could be unconstitutional because the Montana Constitution vests supervision and control of schools in the Board of Public Education. Most opponents said science standards needed to be made by the board and expanded upon by local school boards.

McCall Flynn, the executive director of the Board of Public Education, said any legislative interference with the board’s rulemaking power was a violation of the constitutional separation of powers. She asked lawmakers to table the bill and “seek expertise” from those in the field.

Jenny Murnane-Butcher, the deputy director of Montanans Organized for Education, which supports public education, pointed out that children as early as first and third grade learn to use evidence-based decision-making to learn about the differences between plants and animals, and how chromosome theory works when two parents pass down traits to their children in the Animal Kingdom.

Linda Rost, a Baker science teacher who was the 2020 Montana Teacher of the Year, said the bill would keep her from being able to teach dual-credit classes, bar students from learning enough to take the ACT, and keep them from getting into better higher-education programs.

Braden Burkholder noted that after last year’s flooding in southern Montana, hundreds of scientists – including many with Montana educations – got together in the emergency response to map new river channels, ensure dams were stabilized, and study the erosion and climatological effects. He said those people would not be there in the future if the bill was to pass.

Though there is no fiscal note attached to the bill, during questioning, multiple lawmakers brought up the fact that Montana textbooks would likely need to be reviewed and replaced.

Chris Noel, with the Office of Public Instruction, said the office would need to significantly amend standards to come in line with the law if the measure moves forward. She said she did not know the cost, but was not aware of any standards of adoption that have not cost money.

She also said the process to come up with standards and adopt them would take years.

In his closing statements, Emrich, who was home-schooled, acknowledged some of those concerns and said he would perhaps bring amendments to try to try to get new standards adopted in the current cycle. He also noted the use of the word “indisputable” was in dispute. But he brushed off concerns about the bill possibly being unconstitutional and questions over its purpose. The committee did not take action on the bill Monday.

Jensen, the former Missoula teacher who testified remotely, drew laughs from those who testified, as well as some committee members, as he signed off.

“Oh, and a special shoutout to the quantum theory for making this Zoom call possible,” he quipped.