As fentanyl overdoses surge, education on how to reduce their impacts remains insufficient

This story is being published through a partnership between the Mercury and the Medill News Service.

ARLINGTON – Tricia Obester, an elementary school teacher and mother of a high school freshman, knew fentanyl overdoses were a national crisis. She was also aware that nationally some students were taking drugs. What she didn’t realize was how young some students were when they suffered overdoses. She also never suspected that juvenile overdoses had struck so close to her home.

On Jan. 31, a 14-year-old passed away in the boys’ bathroom of Wakefield High School in Arlington after an overdose. It was the same school where her son studies. Obester said the tragedy was “a definite wake-up call” to her and the community.

Another overdose occurred in an Arlington shopping mall parking garage on March 1. Arlington County Police Department spokeswoman Ashley Savage confirmed that the three people involved were juveniles.

There were no juvenile overdoses reported in 2019, according to Arlington Police Deputy Chief Wayne Vincent. The figure increased to one nonfatal overdose in 2020 and then jumped to eight overdoses in 2022. So far this year, Vincent said that seven juvenile overdoses have been reported in Arlington County.

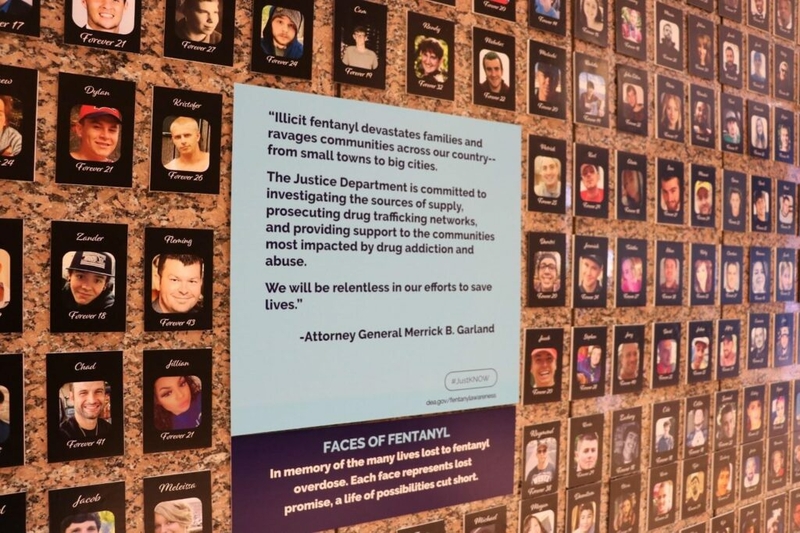

Nationwide, increasing numbers of teens and young adults have overdosed on opioids, especially fentanyl. Fentanyl is now the leading cause of death for Americans ages 18 to 49, according to a Washington Post analysis. Substance abuse experts say educating the public to reduce negative consequences associated with drug use is crucial to prevention. But much of the education that does exist is insufficient. The gaps are especially significant in immigrant and low-income communities.

“The current drug poisoning epidemic is like nothing I’ve ever experienced in my career,” Jon Delena, associate administrator of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration and a DEA special agent for nearly 27 years, said at a congressional hearing in February. “We must do everything we can to stop the crisis.”

Efforts to reduce negative consequences associated with drug use are commonly known as harm reduction. Dr. Neeraj Gandora, chief medical officer for the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, said harm reduction is an important pathway to ensure that patients who may not be ready to engage in full treatment are at least able to mitigate the harms associated with the use of drugs.

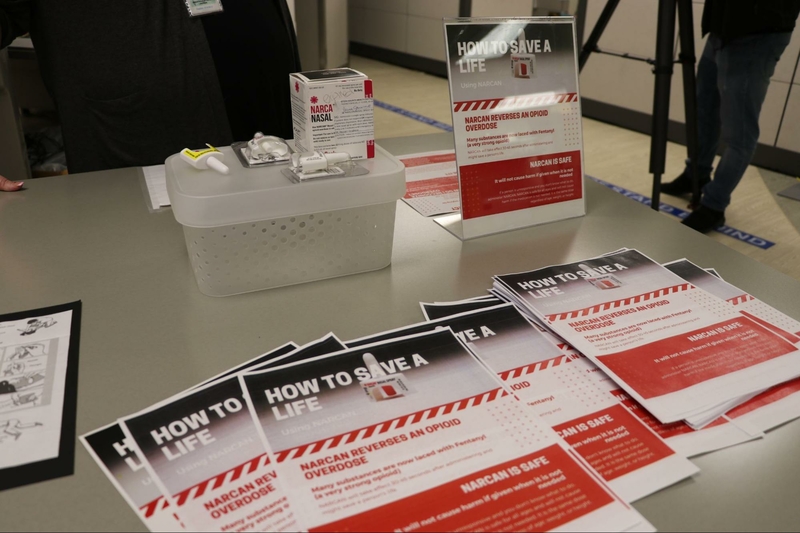

For example, educating the public on how to administer naloxone, a medicine that reverses an opioid overdose, is a crucial element of harm reduction, according to Gandora.

Naloxone can rapidly block the effects of opioids when given in time. There are two forms of naloxone that anyone can use without medical training or authorization: prefilled nasal spray and an injectable version. Nasal spray naloxone is more common because it is needle-free, easy to use and small to carry. It can be sprayed into one nostril of the person who has overdosed while the person lays on their back.

In addition, Gandora said people need to be taught how to spot the symptoms of risky drug use: “If we don’t identify patients, we’re not actually able to get them into treatment.”

In 2021, over 107,000 Americans lost their lives due to drug poisoning, which means an estimated 294 people died of drug poisoning every day, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Two-thirds of those deaths involved synthetic opioids like fentanyl.

Just 2 milligrams of fentanyl, the small amount that fits on the tip of a pencil, can be lethal depending on a person’s body size, tolerance and past usage. DEA seized more than 50 million fentanyl-laced fake prescription pills and 10,000 pounds of fentanyl powder last year. That would be enough to supply a potentially lethal dose to every member of the U.S. population.

Rising demand for naloxone

Arlington County quickly intensified its efforts regarding overdose harm reduction soon after the overdose at Wakefield.

Arlington Addiction Recovery Initiative, Arlington’s opioid and other addictions task force founded in 2017, has held at least one naloxone distribution every week since the beginning of February. The first event lasted only one hour. Three weeks later, it was extended to a whole day in response to the skyrocketing requests for the lifesaving drug.

Participants received a 10-minute, in-person training on how to administer naloxone. After the training, they received a free box of Narcan, a brand name of the most common nasal-spray form of naloxone, and several fentanyl test strips.

The Arlington Addiction Recovery Initiative also provides free online naloxone training and free naloxone by mail.

Deborah Barber, an Arlington County resident, said before the overdose at Wakefield, she hadn’t thought the fentanyl crisis was affecting anybody in her community.

Shortly after the incident, she took a one-hour online opioid overdose harm reduction training. Then she brought her husband and high school-aged son to the in-person training to learn how to administer naloxone.

“This important information should be shared with all of my family members as well,” Barber said.

Access challenges

Naloxone has been available at all Arlington public library branches since last summer.

At Marymount University, located in the northern part of the county, 29 new opioid overdose emergency boxes containing naloxone have been hanging directly next to automated external defibrillators on campus since the end of last year.

But despite such attempts to expand access to the drug, naloxone remains a prescription medicine. That means under federal regulation, adolescents are not allowed to carry naloxone at school.

Jennifer Sexton, a substance abuse counselor with Arlington Public Schools, said she worries that middle school students may not be responsible enough to carry Narcan and may spray it while joking around. But “I do think high schoolers definitely could carry it,” she said.

Staffing shortages make opioid overdose treatment facilities scarce in rural areas and communities of color

WASHINGTON – The message arrived for a young Huntington, West Virginia woman. She had been accepted into an opioid addiction therapy program. The problem was, she had died two days earlier.

Her 2016 death pushed Huntington Mayor Steve Williams to create a quick response team to treat opioid overdoses.

The quick response team has proven to be a game-changer for Huntington. It helped the city lose nasty nicknames given by national media such as “The epicenter of the nation’s opioid epidemic” and “The overdose capital of America.”

Elsewhere in the country, opioid overdose treatment shortages are still prevalent in many regions, especially in rural areas and communities of color. A lack of staff is one of the main reasons.

In rural areas of West Virginia, for instance, shortages still exist, according to research by Joy Buck, a West Virginia University School of Nursing professor. Most addiction treatment facilities are located in urban areas. But West Virginia is largely a rural state, according to the state government. The majority of West Virginia’s 1.8 million residents live in communities of fewer than 2,500 people.

“We need to have [treatment centers] in regions throughout the nation, to have adequate treatment facilities to make sure that we’re doing everything in our power to give an individual an opportunity to be able to come back and be a fully productive citizen again,” Williams said in January at the U.S. Conference of Mayors.

A recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that telemedicine has not expanded access to care for people suffering from opioid addiction. It also found that most patients who used telemedicine lived in higher-income metro areas.

Some communities of color are experiencing the fastest increases in rates of opioid overdose death. But access to opioid and substance use disorder treatment is lower in Black and Hispanic communities.

Drug overdose deaths grew by approximately 30% from 2019 to 2020 in the United States. During the same period, drug overdose death rates increased by 44% and 39% among Black and non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native populations, respectively, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Black and Hispanic people were 3.5 to 8.1 percentage points less likely than white people to complete treatment for alcohol and drugs, according to a report published by the National Institutes of Health.

A cross-sectional study of all 3,142 counties or county equivalents published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found counties with highly segregated white communities had more facilities to provide buprenorphine, a drug prescribed to treat dependency problems.

Dr. Neeraj Gandotra, chief medical officer for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, said his agency has recognized this issue. It requires all new grant recipients to submit a data-driven disparity impact statement outlining how they plan to address behavioral health disparities within their grants.

Gandotra has also introduced several programs within SAMHSA to close equity gaps in opioid overdose treatment.

For example, the agency created a Tribal Opioid Response Program to address the public health crisis caused by escalating opioid and stimulant misuse in tribal communities.

And it created technology transfer centers dedicated to American Indian and Alaskan Native populations and separate ones for Hispanic and Latino populations. The purpose of these centers is to develop and strengthen the workforce that provides prevention, treatment and recovery support services for substance use disorder and mental illness.

“We need to eliminate the racial and ethnic disparities that plagued the overdose epidemic,” said Rep. Robin Kelly, D-Illinois, at a hearing in the Capitol. Her district has become more rural after a recent redistricting.

Even in communities with abundant substance abuse treatment for adults, adolescents don’t have equally sufficient options, said Jennifer Sexton, a substance abuse counselor who has worked for Arlington Public Schools in Virginia for seven years.

“The problem overall is that we don’t have enough people in the field to do the work,” said Mayor Nancy Backus of Auburn, Washington.

Auburn has an opioid overdose treatment center in the city. However, Backus said the staff there suffers from burnout, and the treatment center is desperate for new employees.

Dr. Rahul Gupta, director of the National Drug Control Policy, told mayors from across the country in January that his agency wants to push education institutions to develop more training programs to expand the workforce.

“The problem with that is very few schools today teach addiction curriculum, so the interest never develops,” he said.

Increasingly, teachers and staff throughout the county’s 41 schools are requesting naloxone. Sexton received 20 pages of names within the school system asking for naloxone after recent overdoses. Over 1,000 staff in Arlington Public Schools were trained in ways to reduce negative consequences associated with drug use, especially by administering naloxone.

Last month, two federal panels of addiction experts unanimously recommended that Narcan be made widely available without a prescription. That makes it very likely that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration will approve an over-the-counter version of naloxone.

Dr. Timothy Westlake, an emergency physician from Wisconsin and the primary architect of that state’s prescription opioid strategy, said there are no side effects to naloxone.

“So it’s one of those things where I don’t see any reason … to have a prescription,” he said.

Darrell Sampson, executive director of student services for Arlington Public Schools, said if the FDA approves a nonprescription version of naloxone, it will “give us a different legal landscape from which we can work.”

Teaching students about harm reduction

All Arlington public schools teach students how to protect themselves from drug use beginning in the fourth grade.

Sexton said they teach elementary students how to read a medication label, how to recognize a medication has expired and how to say no when strangers or even other children offer candy or pills. For middle school students and older, they focus on harm reduction for opioids and particularly fentanyl.

Sexton said most students have already been warned by their parents. But some fifth graders appeared scared when she showed them rainbow-colored fentanyl “because it did look so much like candy.”

Not all parents are satisfied with the curriculum.

“The curriculum at the elementary school presently is behind where it should be on the standards that we’re supposed to teach,” said Obester, the elementary school teacher and mother. “The amount of exposure (to drugs) that kids have from older brothers and sisters and from social media … I think is something that was not predicted.”

At the elementary school where Obester works in Fairfax County, teachers found third graders vaping recently. They got the e-cigarettes from older siblings.

“I think the curriculum needs to be updated. I think we need substance abuse counselors meeting with students throughout elementary schools,” Obester said.

Shortages of substance abuse counselors

Arlington, like many other school systems, has a shortage of substance abuse counselors. There are 41 public schools in Arlington with nearly 27,000 students. But there are only six substance abuse counselors.

Sexton, for example, serves two middle schools and 24 elementary schools. Wakefield, the high school with the recent overdose fatality, has over 2,500 students but shares its only substance abuse counselor with other schools.

After recent overdoses, school substance abuse counselors started getting many more requests for education about overdoses and how to reduce their negative consequences.

“There’re a lot of requests for us to do different presentations at different types of community activities, which takes us away from really getting to meet with our students the way that we would like,” Sexton said.

She said it’s difficult to predict which children are likely to abuse drugs. But risk groups include students whose grades suddenly drop and students who suffer trauma, such as divorce or losing a family member.

Some students with mental health issues self-medicate, according to Obester. “This makes sense when you can’t get help otherwise,” she said.

At a meeting at Wakefield one month after the student died, a parent urged the school board to increase the number of counselors. “You have to find more!” the parent shouted to applause.

The shortage of counselors is “a national issue,” said Deborah Warren, deputy director of the Arlington County Department of Human Services. “But we definitely need, honestly, far more resources.”

Warren said the county is coming up with more creative strategies for recruitment, such as paying for substance abuse counselors to move to Arlington and serve the community.

Harm reduction education is disparate

Students and parents are eager for harm reduction education. But they are not the only groups in search of help.

“We can’t just rely on the schools to do something. We can’t just rely on families to do something. It needs to be throughout the community,” Obester said.

Arlington’s immigrant community and low-income families especially need more resources.

In Arlington County, most naloxone training and harm reduction materials, such as flyers and videos, are bilingual in order to serve Spanish speakers.

But in a highly diverse county like Arlington, that still leaves many communities without useful tools. For example, students at Hoffman-Boston Elementary School come from 47 countries. Not all their parents are proficient in English.

Warren said it is particularly hard to find counselors who speak the many languages spoken by Arlington families. Arlington Public Schools has even posted ads in Puerto Rico in an attempt to recruit bilingual counselors.

We can't just rely on the schools to do something. We can't just rely on families to do something. It needs to be throughout the community.

The challenge is even greater on the West Coast, in communities such as Orange County, California, which is home to many Chinese immigrants.

Various community-based organizations have started to provide opioid harm reduction to non-English speakers in Orange County. For instance, the Asian American Senior Citizens Service Center printed postcards in Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean and other Asian languages that describe the symptoms of overdoses and how to use naloxone.

In order to educate immigrant communities, it’s not enough just to translate the language. “It also means the cultural consideration and the multicultural piece to really understand the nuances behind it and how you can better reach that population,” said Luna Lu, a mental health clinician with the center.

Because government officials may not be able to reach every group in a diverse area, community groups that represent different cultural backgrounds may be a more effective way to reach diverse populations, said Lu.

“We are the tentacles in the community,” she said. “And we are more than willing to fill those holes.”

But she complains that funding is scarce. The Asian American Senior Citizens Service Center has to spend its limited funds on public information campaigns. The only donation it received for this effort was 1,000 boxes of Narcan that it received for free via a website called narcandirect.com.

Arlington Addiction Recovery Initiative received $70,000 this year from Virginia’s State Opioid Response Grant for opioid overdose prevention, according to Emily Siqveland, the opioids program manager of the Arlington County Department of Human Services.

She said that’s enough for most of their campaigns, such as Narcan distribution and advertisements on TV, public transportation and social media apps. But more would allow the department to expand its overdose education offerings.

Siqveland said in her dream world, Arlington Addiction Recovery Initiative would work like a music band, “driving around, doing these trainings in different neighborhoods.”

“If we here in Arlington County, one of the richest counties in the country, can’t access the funding and put this in place and help our students pass the disaster … then I don’t know who can,” said Obester.