Fear mongering on crime failed; now Democrats can get to work on true public safety

Last month, Minneapolis and St. Paul each installed new police chiefs. A coincidence not only that each city had a leadership succession around the same time as each other, but also in that the changing of the regimes occurred shortly after an election season in which Republicans focused their campaign on policing and crime.

It wasn’t the first time political campaigns hyped urban crime with the hope of scaring those who do not regularly experience urban life, simultaneously seeking to prey on preconceived racist fears. But, in Minnesota, that left too many suburbanites — an increasingly diverse lot — who knew from their own experiences that public safety problems in the cities came nowhere close to the extremes Republican messaging wanted them to believe. So the campaign was a failure.

Public safety issues do motivate voters if they are presented with distinct policy choices, and not just oversold fear. While Republican policy prescriptions for crime are typically abstract — let’s better support our police! — the 2021 Minneapolis city elections appeared to many to present real differences for public safety and policing. While some of that campaigning also leant itself to exaggerations (or, as some would argue, falsehoods), at least many voters were able to connect the choices before them with their own experiences of crime and policing. As it turned out, the approach to policing considered more traditional and cautionary won when voters rejected Question 2, which would have created a new department of public safety.

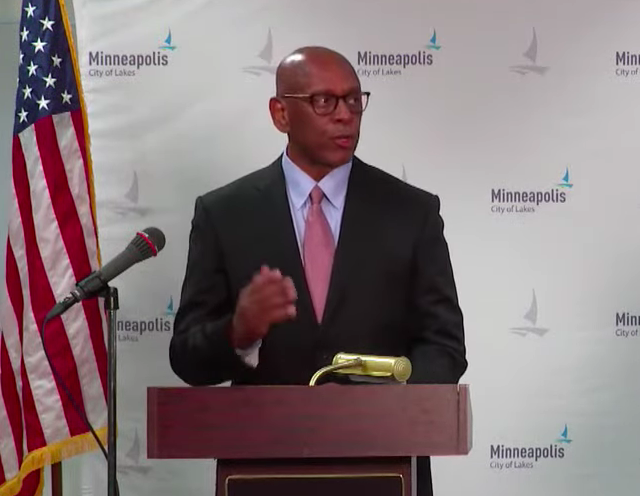

Minneapolis under Frey seems to be doing much of what reformers sought when in opposition to him during last year’s city election.* An umbrella community safety department has appeared with a leader above the chief of police (Commissioner Cedric Alexander), and with the goal of uniting public safety strategies in a manner that may lead to better specialization of 911 response than the police-only model. Bringing in Brian O’Hara, a police chief whose frame of knowledge extends beyond being a Minneapolis cop, or even just a cop — he held a deputy mayor position in Newark — appears consistent with prioritizing open mindedness about deeper reforms.

There really is far less to say about St. Paul, whose police have a different public perception than Minneapolis. The SPPD does not come close to the MPD’s history of controversy, nor has it experienced calls for sweeping external investigation of its practices, or U.S. Department of Justice or Minnesota Department of Human Rights consent decrees. Accordingly, they continued the longstanding practice of promoting their new chief, Axel Henry, from within, the goal being to stay on course. What bears watching in St. Paul is whether experiments that go well in the MPD or elsewhere lead to enhancements that are accepted equally well by the SPPD.

At the state level, it will be interesting to see how the DFL approaches policing and crime now that they control the Legislature, albeit with a narrow majority in the Senate.

In the early aftermath of the George Floyd murder, the legislative focus was entirely on police accountability and not crime, and the most tangible changes that could successfully be negotiated with Republicans involved the strengthened role of the Police Officer Standards Board and refining the limits on the use of deadly force. Last session, as public safety concerns became elevated in advance of the election, the compromise worked out would have brought enhanced funding both in support of police recruitment and for alternatives to police response. Republicans ultimately revoked their support of this compromise, which appeared to be a component of the election strategy that is now seen as a failure; if no public safety bills passed the Legislature, then it could be said that Democrats were not doing anything about crime.

The 2022 bill was co-sponsored by Rep. Cedric Frazier, a New Hope Democrat – and key ally of new Hennepin County Attorney Mary Moriarty, who was also subject to a “weak on crime” campaign that failed miserably. It bears watching if the bill will be reintroduced in the compromise form that had the initial Republican signoff, or will be rewritten to better reflect the preferences of a DFL-controlled Legislature that may not need any Republican votes.

Meanwhile the new police chiefs should have far greater impact for strategies that improve police accountability and public safety. If they succeed, it will likely be because they recognize this paradox of policing and make all of their decisions with both of the following in mind:

For police to function effectively as an instrument of crime reduction, they need to be widely supported by the public they serve.

For police to be widely supported by the public they serve, they need to function effectively.

The failed Republican campaign ignored the second part, ducking the question of how police could be more effective and blaming those who did not support police as if they had a character flaw and not reasons.

But police work — not just recruitment — is far more difficult when people don’t respect or trust cops. Police need cooperating witnesses and helpful information. When disdain and distrust are prevalent, police rely on profiling to try to find weapons, drugs or other luckily spotted evidence of crime, which is carried out with disproportionate racial impact — and then further fuels distrust and disdain. This becomes a negative feedback loop, with collapsing support for police lessening their effectiveness, which leads to still less public support.

The tension within the DFL may come from internal pressure to ignore the first part of the paradox, that to be effective police must have broad public support. Some at the radical edges of the DFL base, even if they tolerate police as a necessity, cringe at overtly supporting them. Not just based on recent scandalous behavior or even the frustrations from decades of failed accountability, but as a matter of principle of some sort.

Contrary to the insinuations from Republicans in the recent campaign (or the similar failed attack on Moriarty), elected Democrats support police as an institution, and should be seen in good faith as wanting police to be both effective and supported.

How to best move towards policing that is simultaneously effective and supported is a challenging question that is open to debate. And which will require experimentation, including some approaches that may yield beneficial results and some that may not end up working as well as intended.

With Democrats in the Legislature not needing to compromise with Republicans who refuse to consider questions of police effectiveness, a new Hennepin County attorney joining the Ramsey County attorney in having an interest in innovation, and new police and community safety leaders in Minneapolis similarly motivated, the opportunity to make true advancements in public safety is far more possible than had the “public safety champions” won.

Though most commentators believe the election results show that crime and policing were not the priority for voters, the election results have at last allowed crime and policing to be a reachable priority.

*Correction: Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this article misstated Frey’s position on creation of a department of public safety.