Board of Education hears more comments on proposed social studies standards

The public had a second opportunity to speak to the South Dakota Board of Education about proposed changes to the state’s social studies standards on Monday at the Sioux Falls Convention Center.

The in-person comment session came after nearly 1,000 people submitted written testimony, and dozens of educators braved the cold to protest the document.

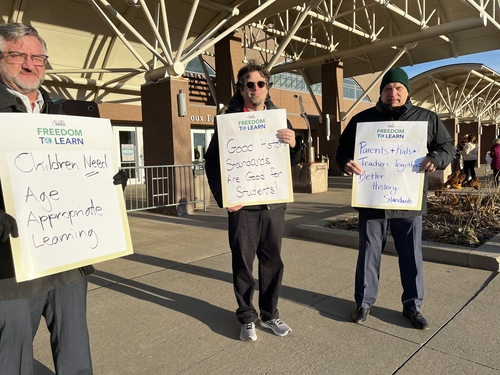

Opposition was apparent even before visitors entered the building, as about a dozen protestors carrying signs stood outside.

Inside the convention center, proponents of the standards spoke first, with concerns ranging from supposed Marxist indoctrination and kids using litter boxes in schools to beliefs that the new standards would increase national pride and Native American representation.

Larry Fossum said that he was disappointed that the first draft of the new standards had little mention of Native American history, but said the reworked version of the standards are rich with that history.

“We finally have a social studies standard that would lead this nation by example and begin to represent all the people of the state,” Fossum said.

South Dakota tribes disagree.

Brian Wager, an education consultant for Crow Creek and education director for Lower Brule, said all nine tribes in the state oppose the new standards.

“The social studies standards, in regards to Native Americans, are missing for great spans of time as if Native Americans didn’t and don’t exist,” Wagner said.

Other opponents argued that the new standards are reductive and replace doing social sciences like geography and history with the memorization of names and dates.

One said reducing history to memorization isn’t educational.

“These standards focus on history as a series of things to memorize, rather than to think actively and critically,” said Stephen Jackson, who teaches history at the University of Sioux Falls.

While the curriculum does challenge students to memorize a lot of information, proponent and South Dakota State Historian Ben Jones said, that memorization sets them on a path to deeper understanding at higher grade levels.

“The proposed standards build knowledge in the early grades so that students have something to think critically about as their knowledge is building,” Jones said.

Few current South Dakota educators spoke in favor of the new standards. The educators backing the standards were largely retired or worked for private, out-of-state charter schools – something opponents like Rob Monson found frustrating.

“Where is the evidence that what we are doing in South Dakota and how we are doing it isn’t working?” said Rob Monson, executive director of School Administrators of South Dakota.

Originally, the social studies standards were crafted by a more than 40-person work group.

That initial proposal was scrapped around the time Hillsdale College of Michigan began to work with former president Donald Trump’s staff on classroom materials designed to counter so-called “anti-American indoctrination” in education. Those materials were the starting point for a 15-person work group, which included a retired Hillsdale educator, to begin work on the standards up for debate now.

The Department of Education said it collected 968 comments regarding the new standards — 103 are in favor, 828 are opposed. The rest are neutral.

That disparity was mirrored at the convention center. When opponents were asked to identify themselves in the room of about 250 people, nearly every attendee stood.